I got some insight into what kind of temperament one needs to sustain a 60 year career in documentary when I asked Fredrick Wiseman what I imagined to be a fair question: What recent trends in documentary film do you find heartening or perhaps disheartening?

"I don't go to films. I mostly read."

I pressed him: "You don't watch films? When you go to film festivals or these kinds of events?"

"I still read. There are hundred of years of literature to choose from. I prefer that."

I plopped down. Was that a dumb question? Was that an arrogant answer? Should I take this personally and title this blog article "Wiseman to Aspiring Documentary Filmmakers: Drop Dead"?

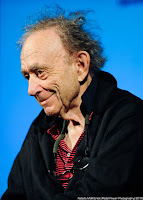

I wasn't the only questioner at The Doc Yard's screening of "Hospital" (1969) who didn't get far with documentary director Fredrick Wiseman . The host, an academic in film studies, had his first question brushed aside as well, and he was forced to regroup and find another angle.

. The host, an academic in film studies, had his first question brushed aside as well, and he was forced to regroup and find another angle.

But I was personalizing it. There was a lesson here from documentary zen master Wiseman. (who, in fact, looked more than a bit like Yoda) Wiseman embodied the essential quality one needs in order to sustain a long career in documentary: the executive ability to say "No" and move on quickly . One needs a ruthless internal compass to guide you through the brambles of distraction, which are intent on taking you down blind alleys. That ability to make quick calls, to dismiss the distracting or extraneous - either in interviews or while slogging through millions of feet of footage - is essential. Because you need to stay on track - have a sense of the scope and form of the work - or you get lost quickly.

It may be inaccurate to call these decisions "judgement calls", because it is not like Wiseman was passing moral or intellectual judgement, calling a question stupid. He just didn't want to go there. That's the Zen part. A piece of marble that a sculptor chips from the block isn't "bad", it just doesn't belong in the piece. In fact, it might have been a great question, but if you've ever edited a film, you know that there are always going to be great scenes that you remove simply because they didn't fit in the larger piece. The scene might have taken all day to shoot. It might have cost a lot of money. It might be hilarious. Faulkner called these bits "darlings", and said "Kill your darlings" - when they don't serve the whole. Pirsig wrote that there is a third way to answer a yes or no question: the Chinese character "Mu", which means "Unask the Question".

wrote that there is a third way to answer a yes or no question: the Chinese character "Mu", which means "Unask the Question".

Apart from the ability to stay on point, Wiseman also exemplified the kind of self-reliance needed to survive. He had a distributor for his first two films, but when he found out they were ripping him off, he sued them. (And got some money back). Since then, he has self-distributed his work: "If it fails, I know that it is my fault that it failed."

Along these lines, the experience of "Titicut Follies " may have been a defining moment. It was Wiseman's second film, and it was immediately censored and not allowed to be shown in public. For 24 years, Wiseman soldiered on, step by step, in his legal battle for the film's release. From being initially banned, the film was allowed to be shown to credentialed medical professionals. Wiseman then argued that he could not be responsible to check the ID's of people at screenings. He won that motion, and the film was allowed screenings in University settings without viewers being required to sign a form. (That's how I first saw it, at Wesleyan University back in the 80's). Eventually, all censorship was dropped. But how many filmmakers would have thrown in the towel rather than fight for the film (and the First Amendment, for that matter. Titicut Follies still has the distinction of being "The only American film banned from release for reasons other than obscenity or national security".

" may have been a defining moment. It was Wiseman's second film, and it was immediately censored and not allowed to be shown in public. For 24 years, Wiseman soldiered on, step by step, in his legal battle for the film's release. From being initially banned, the film was allowed to be shown to credentialed medical professionals. Wiseman then argued that he could not be responsible to check the ID's of people at screenings. He won that motion, and the film was allowed screenings in University settings without viewers being required to sign a form. (That's how I first saw it, at Wesleyan University back in the 80's). Eventually, all censorship was dropped. But how many filmmakers would have thrown in the towel rather than fight for the film (and the First Amendment, for that matter. Titicut Follies still has the distinction of being "The only American film banned from release for reasons other than obscenity or national security".

Wiseman told the audience that the essential qualities documentary filmmakers needed was luck, judgment, and patience. I'd add courage and character - and not shutting off the camera when the going gets gross. Hospital has perhaps the longest scene of projectile vomiting in motion picture history. A lesser cameraman and director might have fled the scene, or cut the material for the sake of "good taste" (even today, people leave the theater) But if Wiseman had punked out, audiences would have been denied one of the most outrageous moments in film history, and the funniest line about Art Majors, ever.

An earnest young woman asked about the ending of the film, which showed doctors, nurses and patience in the hospital chapel, praying, offering tithe. She said "I have two reactions to that - the first is that you are being cynical. The other is that you are saying that religion gives these people hope for the future, and helps them get through their problems."

Wiseman's response: "Can't I be saying both things?"

Om.

"I don't go to films. I mostly read."

I pressed him: "You don't watch films? When you go to film festivals or these kinds of events?"

"I still read. There are hundred of years of literature to choose from. I prefer that."

I plopped down. Was that a dumb question? Was that an arrogant answer? Should I take this personally and title this blog article "Wiseman to Aspiring Documentary Filmmakers: Drop Dead"?

I wasn't the only questioner at The Doc Yard's screening of "Hospital" (1969) who didn't get far with documentary director Fredrick Wiseman

But I was personalizing it. There was a lesson here from documentary zen master Wiseman. (who, in fact, looked more than a bit like Yoda) Wiseman embodied the essential quality one needs in order to sustain a long career in documentary: the executive ability to say "No" and move on quickly . One needs a ruthless internal compass to guide you through the brambles of distraction, which are intent on taking you down blind alleys. That ability to make quick calls, to dismiss the distracting or extraneous - either in interviews or while slogging through millions of feet of footage - is essential. Because you need to stay on track - have a sense of the scope and form of the work - or you get lost quickly.

It may be inaccurate to call these decisions "judgement calls", because it is not like Wiseman was passing moral or intellectual judgement, calling a question stupid. He just didn't want to go there. That's the Zen part. A piece of marble that a sculptor chips from the block isn't "bad", it just doesn't belong in the piece. In fact, it might have been a great question, but if you've ever edited a film, you know that there are always going to be great scenes that you remove simply because they didn't fit in the larger piece. The scene might have taken all day to shoot. It might have cost a lot of money. It might be hilarious. Faulkner called these bits "darlings", and said "Kill your darlings" - when they don't serve the whole. Pirsig

Apart from the ability to stay on point, Wiseman also exemplified the kind of self-reliance needed to survive. He had a distributor for his first two films, but when he found out they were ripping him off, he sued them. (And got some money back). Since then, he has self-distributed his work: "If it fails, I know that it is my fault that it failed."

Along these lines, the experience of "Titicut Follies

Wiseman told the audience that the essential qualities documentary filmmakers needed was luck, judgment, and patience. I'd add courage and character - and not shutting off the camera when the going gets gross. Hospital has perhaps the longest scene of projectile vomiting in motion picture history. A lesser cameraman and director might have fled the scene, or cut the material for the sake of "good taste" (even today, people leave the theater) But if Wiseman had punked out, audiences would have been denied one of the most outrageous moments in film history, and the funniest line about Art Majors, ever.

An earnest young woman asked about the ending of the film, which showed doctors, nurses and patience in the hospital chapel, praying, offering tithe. She said "I have two reactions to that - the first is that you are being cynical. The other is that you are saying that religion gives these people hope for the future, and helps them get through their problems."

Wiseman's response: "Can't I be saying both things?"

Om.

Nicely written! I saw la Danse and loved it. Did you ask him your question by email? was it hard to get through to him?

ReplyDelete